1: Tech = unoriginal, lazy, consensus, etc

Discussing and debunking some of the popular criticisms of large cap technology shares

One criticism frequently levied at investors and fund managers who hold a lot of large-cap tech stocks (FANG / FAAMG / FANMAG i.e. some combination of Facebook, Apple, Google, Microsoft, Netflix, occasionally lumped in with other largecap Internet-beneficiaries such as Visa, Mastercard, PayPal, Adobe and the like) is that the investor or fund manager must be lazy, lacks original thinking, or too easily bends towards consensus. An example is below:

I admit that it may look odd to an average observer at first glance if an investor or manager represents him/herself as an independent thinker and simultaneously holds a portfolio filled with the largest Internet-beneficiary stocks. The critics usually single out portfolios like the ones below:

I am bemused by these criticisms. There is a small grain of truth to them but overall the criticisms are simplistic, not entirely well thought-through, or at least are poorly articulated. Here is why:

1) Results matter.

I am peeved when anyone is fixated on perceived virtues such as originality but results do not feature as highly in the person’s discussion.

First and foremost the job of an any professional investor is preservation of capital and a delivery of satisfactory long-term compounded returns relative to the amount of risk taken. Full stop. Over the long-term, results trump everything else. This is not to say that an investor who makes very foolish probability-adjusted bets (like exclusively buying lottery tickets) and ends up with very high returns should be admired. Not at all. Still, there is nothing noble or worthwhile about appearing to the outside world like you are doing a good job through some imperfect indicators such as statements or demonstrations of originality, deep experience (“our team boasts a combined 100 years of experience in the investment business”), conscientiousness (“on average we speak to at least 5 management teams a week” and “for any new investment we conduct at least 10 hours of expert network calls”) or contrarianism yet failing to deliver for years on end, while continuing to charge hefty management fees and exposing clients to tax inefficiencies from the continued dashing from one proposition to another.

2) What other people have and haven’t thought about is difficult to assess from a distance.

If an investor is substantially long large-cap Internet beneficiaries, does that automatically really mean that the investor is lazy or failed to turn over many rocks? Of course the answer is no. There is not much correlation between those things in a professional setting, in my experience. What it can mean is that these investors have different philosophies, apply different mental filters, possibly pursue different research processes, and probably operate under different business restrictions (e.g. how their business development people market them to their clients; whether they are offshore funds with few restrictions, ‘40 Act or UCITS funds; whether they have any active share and concentration limits; etc). How can a critic look at another investor holding lots of FAMG and nonchalantly yet confidently conclude that the investor has never sufficiently entertained buying shares in an anything else, be it a dry bulk shipper, Baidu, Cimpress, Viacom, Expedia, Oracle, a junior gold miner, a SPAC, an oil major, Sberbank, bitcoin, etc? This is a ridiculous notion, clearly.

Grab a coffee or go out for drinks with any professional generalist equity investor adhering to any kind of investment philosophy and quickly you will find out that he/she probably looked at and eventually passed on a surprisingly lengthy and eclectic range of businesses. Of course, it’s possible that you will come across an investor or two who may exclusively fish in the pond that is the intersection of only TMT businesses and only businesses that quantitatively and qualitatively above-average, and completely dismiss everything else (“I don’t know anything about energy, biotech, airlines and brick-and-mortar retail, and don’t really want to find out”). But how can anyone know enough about other investors to judge what they know and what they passed on in an informed manner, from a distance?

Maybe we shouldn’t judge a book’s author by its cover.

3) “Consensus” is a misapplied term.

We all start with the notion that if you do what everyone else does, you will get results that are “average”; if your portfolio closely resembles the S&P500 in constituents and their weights, your returns will be close to the returns of the S&P500. This is reasonable. Before we examine the meaning and mis-use of the term “consensus” allow me a quick sidebar on some more technical terms. The way fund allocators and consultants frequently evaluate this is by measuring an investor’s gross active weight (a sum of the absolute % weight deviations for portfolio securities against their benchmark weight; can have any value from 0 to 200) or active share (gross active weight divided by 2; can have any value from 0 to 100). An active share metric above 60 is considered as active; 0 is passive; anything in between is usually considered closet indexing. These metrics are imperfect but they are convenient in that they try to boil down an investor’s overall “originality” to a single number that you can easily compare others against.

Now take another look at investors or funds that get criticised for being long lots of large-cap Internet beneficiaries and examine their weights. For instance, take the 13F that I shared above (from ‘Act Two Investors LLC’). Its active share metric is c.75, i.e. this fund is rather ‘active’. Not only does this fund own lots of large cap tech / Internet beneficiaries, it owns relatively little of anything else. As a reminder, below are the current top weights of the S&P500 index.

If you run the numbers, you will find that a theoretical portfolio that is simply long Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook and Google and nothing else (i.e. 20% AAPL, 20% MSFT, 20% AMZN, 20% FB and 20% GOOG or GOOGL) has an active share of 75.9, which is considered pretty damned ‘active’. I believe for most professional investors, psychologically and from a business perspective it is very challenging to maintain a portfolio with this level of concentration and active share.

Imagine that tomorrow everyone in the investment business is reset to a starting pot of $100 million cash and is asked to construct a portfolio using the 500 constituents of the S&P500. Of course, the ultimate investment results of any investor will depend not just on which of the 500 stocks he/she picks, but also how he/she decides to weight them. And somehow, even if some of the investors pick mainly large-cap Internet beneficiary stocks like Microsoft or Facebook and weigh their picks in such a manner that the active share is high, there will always be a contingent of critics on the sidelines dismissing these investors as lazy, unoriginal consensus thinkers. So perhaps there is something different at the core of their disagreement?

4) Attacking the wrong targets.

It’s almost as if in the eyes of the critics, being long large-cap tech Internet beneficiaries is a less ‘worthy’ way to conduct one’s investment portfolio. If we keep peeling back that onion, usually we’ll find the critics shifting to the following arguments, listed in an increasing order of sophistication:

“These largecap tech stocks are trading at ridiculous multiples, are overvalued, and/or are in the midst of a massive bubble.”

“Everyone already knows everything there is to know about Facebook/Microsoft/Apple/etc; e.g. everyone knows they are great businesses, they get tons of analyst coverage, even my barber/brother-in-law owns them, and everyone loves them. They cannot continue outperforming.”

“These largecap internet businesses are exhibiting the growth factor (in the style of Fama-French ‘high minus low’). The differential in performance of the growth factor versus the value factor is at very high levels versus history and is at acute danger of reversing. It’s likely that growth’s outperformance is powered by the huge liquidity injections from the Fed and falling interest rates that enhance the valuations of businesses that are expected to have greater free cash flows far out into the future.”

“These largecap Internet beneficiaries are already so large (some at trillion $ or multi-trillion $ market caps). Surely trees cannot grow to the sky.”

“The levels of economic rent extracted by the largecap Internet beneficiaries are unsustainable and are bound to revert closer to the overall mean through either market forces of competition or more far-reaching regulation, break-up or taxation.”

“These largecap Internet beneficiaries by virtue of their size, membership in the right sub-indices and lack of obvious anti-ESG / divestment stigma, have been disproportionate beneficiaries of passive fund flows and thus their strong share price performance is unsustainable.”

You, the reader, have probably experienced your own versions of these debates countless times before. I am gradually coming around to the notion that instead of just stating my own view / conclusion on the subject (even if it is an exasperated “nobody knows anything” and “we should all just stick to an investing style that fits our own objectives and personality”), it is a worthwhile exercise to try to engage the critics in a deeper discussion, ideally starting as far back as raw data and first principles. The diagram below is a useful self-reminder on that front.

Now let’s deconstruct each of the deeper arguments in turn.

“Overvalued”.

If we follow the logic of the diagram above, before jumping in to refute the point above that the largecap tech beneficiaries are trading at “ridiculous multiples” or are “overvalued”, it is sensible to first take a step back and examine the data and the assumptions. Go on a sort of ‘journey’ with the critic. What metrics (earnings multiple? FCF multiple? price to book? etc) as well as what time periods is the critic focused on? Bedrock valuation principles (i.e. the intrinsic value of an equity claim on a business is worth the discounted future unlevered free cash flows less all senior claims, yada yada) might need to be re-established because surprisingly often the critic might disagree on some seemingly uncontroversial things even at this foundational stage of the discussion. For instance, some people will resist looking even 2 years into the future to evaluate a free cash flow multiple and compare it to the opportunity set, and some are unwilling to consider that it is reasonable to pay a lower free cash flow yield for a business if your certainty level on the long-term projections is a lot higher for this particular business and the business requires very little incremental capital (and might in fact be returning 100% of the incrementals each year).

The discussion may also be framed in the form of the Grinold-Kroner (“stocks as bonds” is how I call it though I am not aware of either Grinold or Kroner describing their formula that way) approximation of equity returns. A version of that equation is applied by BCG in much-referenced report (discussed in a Tweet below) that illuminates the high importance of revenue growth over longer time periods.

Breaking those things down to the building blocks helps articulate the expectation for a % compounded equity return from continuing to hold these largecap Internet beneficiaries like Microsoft / Facebook / etc. Here it is reasonable to concede that most of these businesses have experienced significant multiple expansion in recent years. But if these businesses were rather cheap a few years ago, just because the multiples have expanded does not mean that the businesses are not cheap still. In my estimation, for at least a few of the largecap Internet beneficiaries a low to mid-teens % IRR if held over multiple years is still available using assumptions that are not particularly heroic.

If the IRR is framed using Grinold-Kroner, the critic will probably take issue with the exit multiple assumption unless you already are baking in significant contraction. Here the discussion must necessarily shift to the qualitative specifics of the business model and sustainability of the economic rent that it is extracting. While the exact % ROCE metric 10 or even 5 years from now is difficult to predict, there is research that supports persistence of return on capital metrics by business quartiles. But the bulk of the discussion probably has to be business and industry-specific.

“Too popular and well-known.”

Whether a stock is popular, well-covered by sell-side, well-known, widely held by retail or “overowned” by institutional investors should have zero bearing on the underlying business fundamentals and how we value the business using the methods discussed in the prior section, above. You could make a version of the Soros argument or reflexivity that if a stock’s increasing ‘popularity’ helps drive multiple expansion then the portion of the stock rise that comes from multiple expansion will influence the underlying fundamentals, but that argument is stronger when the business in question is a prodigous user of capital markets; this is more the case with capital-consumptive businesses or businesses engaging in lots of sizeable M&A that require share issuance. By and large these (in my view, somewhat negative) characteristics do not apply to the very largest Internet beneficiaries. The fundamentals will drive the intrinsic value and share price performance over time. I prefer this truth to the other classic way of dispelling the ‘popularity’ criticism i.e. you could have said the same thing about Microsoft and Apple 1, 3 and 5 years ago (“they are popular; everyone knows everything there is to know about them; they are widely covered by sell-side” etc) yet their shares strongly outperformed.

“Growth factor / interest rate risk”.

There is some truth to this criticism. But note that declining interest rates and increasing Central Bank liquidity have likely benefited the entire equities asset class (though maybe not banks), not just the Internet stocks, even if the ‘growthier’ businesses benefited more by virtue of having greater terminal value importance to their intrinsic values.

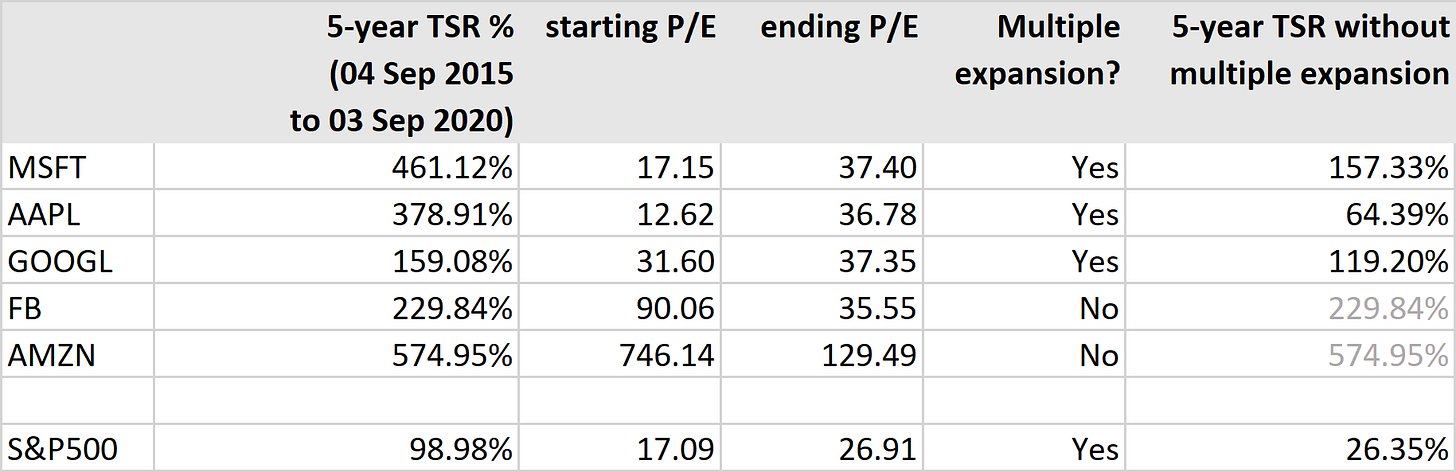

Below is an interesting experiment - if we remove the multiple expansion component of the returns of the top 5 S&P 500 weights (Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google), their returns still have beaten the S&P 500 by a wide margin.

In other words, their profit growth, inefficiently underlevered capital structures (for Apple especially) and low starting multiples (i.e. high impact of buybacks) were sufficient to drive rather good returns, even if you had not relied on multiple expansion. This is not to say that returns starting from today will be as good as they have been in the past 5 years. For instance, take Apple and its buybacks. Holding everything else equal and assuming 100% net income conversion to levered FCF and if Apple spends all of its net income to repurchase shares, buybacks at 36x P/E only grow Apple’s EPS by 2.7% vs the 6-8% accretion that Apple had in the last few years when its P/E multiple was lower.

If you are long a growing business with significant long-term franchise value, it is sensible to realize and freely admit that in some ways you are long a rates ‘flattener’ due to the terminal value aspect of intrinsic value. But (i) if you believe your attitude is that of a long-term business owner, (ii) if the business is of high quality, (iii) if the business has the power to pass-through cost inflation and (iv) if your long-term exit multiple assumptions are reasonable, then there do not seem to be drastic reasons to sell the shares just because of the interest rate and Fed arguments.

“Trees cannot grow to the sky”.

“Microsoft is already worth north of $1.5 trillion, how much bigger can it get”, or so goes the refrain. To a certain extent, I think we all struggle to adequately picture very big numbers and everyone is susceptible to over-extrapolating high growth rates too far into the future. That said, nothing changes the truth that a business is worth its long-term discounted future cash flows. Thus, if the cash-flows are not expected to rapidly decay (due to still substantial growth or thanks to very low reinvestment needs) or the discount rate is low due to higher-than-average levels of certainty into those cash flows, the business can be worth a lot more than an average business. Especially if the business in question is leveraged to the Internet, is attacking very large addressable markets, or is displacing very large existing spend yet can sustainably extract greater margins and return on capital than the current competing businesses whose spend it is displacing due to a superior business model, certain virtuous cycles in operation and ability to constantly pass on some new surplus to the consumer. Another way to look at it: a $100 billion of revenue currently owned by a total of many smaller, more fragmented competitors operating an inferior business model converts to a lower aggregate EBIT and lower % ROCE than what an Internet platform business will generate once that $100 billion of revenue is siphoned off by the platform. The platform will also have greater ability to cross-sell and the incremental EBIT that is being spat out by the extra $100 billion of revenue earned by the platform should be capitalized at a higher multiple. There were probably some seeds of truth in the DotCom mania before it went too crazy. The world is a big place, and the Internet and software business models have proven to be more powerful than many people thought even a few years ago.

“Competition and regulation will revert the returns to the mean.”

It is not easy to generalize these risks for the whole large-cap Internet space because the situation is different for each of the players. I am not sure there is a more effective way to manage this risk other than having appropriately conservative assumptions across the board, including revenue growth, margins and incremental margins, exit multiple, and tax rates. Some investors make bullish points that break-up or spin-off scenarios are actually beneficial for some of these business values (e.g. Amazon shares) but there are too many open questions for me still to have a view one way or another.

“Flow beneficiaries.”

It is logical that large-cap tech platforms are at least partial relative beneficiaries of the drive to divest from anti-ESG sectors (tobacco, guns, hydrocarbons) as the divested dollars have to go somewhere. Their large weights in market cap weighted indices may also be fueling virtuous circles of further tech market cap growth from passive inflows, as active managers who won’t or can’t hold the index weight of these tech ‘champions’ get redeemed and that capital is invested in passive. These arguments are all reasonable though they are difficult to measure. I guess the questions that they raise is whether large cap technology platforms will be meaningfully damaged by any structural reversal of passive flows, and when that reversal is likely to get underway (and how long it may last). Finally, is it possible to measure the theorized current benefit to large-cap tech from passive in a credible way? The multiple expansion table I present above shows that the FAAMG businesses delivered attractive (at least, superior to S&P500) total shareholder returns even absent multiple expansion; the benefit from passive would show up in incremental multiple expansion.

Summary and open questions.

Three conclusions crystallized further in my mind as I was writing the above:

(i) it is very challenging but very important to try to keep an open mind to everything. Rules of thumb and blanket dismissals of anything are dangerous. We are all learning as we go. And the more we learn, the more we realize that we actually don’t know much.

(ii) everybody should stick to an investment approach that suits their own objectives and their own personality.

and

(iii) almost none of what I wrote in this post really makes sense unless you utilize longer time periods, i.e. time periods during which the quality of the business, the industry dynamics, the decision-making of management and the principal/agency structure impact the equity value. In the short term, anything can happen.

Wonderfully articulated Brosef - great insights!

Warmly,

Soumil.

Great read. thanks